Blog

An Ounce of Prevention: The Food Safety Act Wants to Catch Outbreaks Before They Start

This blog post is a 13 minute read

Food safety inspections are an important part of the industry that grows, produces, and distributes our food.

About one in six Americans—around 48 million—get sick every year from foodborne illnesses. Even more alarming nearly 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 people die each year from foodborne diseases according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Strengthening our food safety system is intended to save lives and reduce illness. Industry participation with federal regulators’ oversight is central to a functioning system, but the complex regulations themselves can be confusing.

The history of food safety in the United States provides some context as to why such programs are needed but unwinding the webs of federal rules to determine who is covered by which regulations and how they will be implemented can be tricky. In this post, we’ll look at what the Food Safety Modernization Act is, what the key provisions of it are (and who is affected), and how to build a smart risk-based program that incorporates best practices for managing microbial, chemical, and physical hazards at your plant.

What is the Food Safety Modernization Act?

The Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) is the first major overhaul of the regulations governing food safety in the US since 1938. It was passed into law in 2011 and signed by President Obama. Like many federal laws, the name is a bit unwieldy and so it is often referred to as the Food Safety Act or the FSMA—just as we’ll do in this piece.

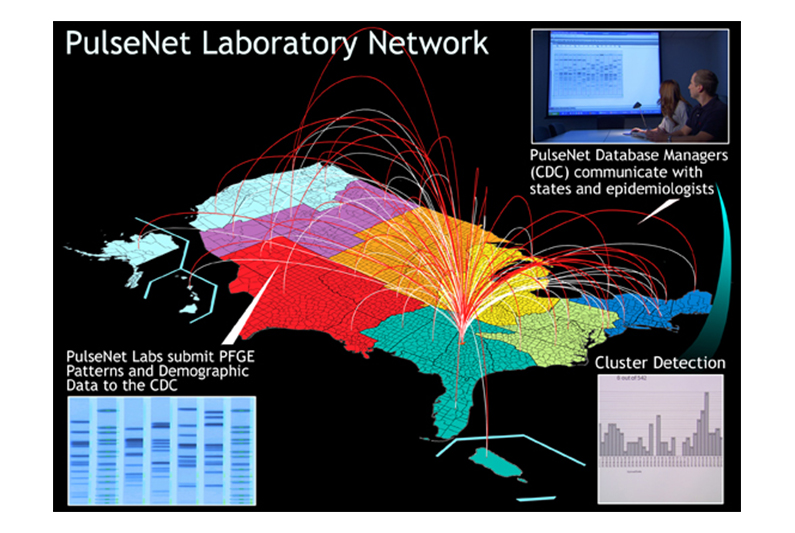

Microbes causing food-related illnesses have a DNA profile that allows trace back to the raw material and to the manufacturing plant doing the packaging (click above to view full version).

There were a few factors that led to the belief that legislative changes were necessary to update the laws that governed food safety. The advent of several high-profile incidences of widespread foodborne illness outbreaks—that included such diverse products as Salmonella in peanut butter, and issues with raw juices, honey, farmed fish, hamburgers, fresh spinach and cookie dough—and potential vulnerabilities that might exist in our food system that might make it susceptible to bioterrorism were big concerns.

Identifying these risks and concerns and then proposing legislative fixes for them on this scale takes time. Changes were first introduced and debated in 2009 and 2010, leading to the creation of working groups, a task force, and a lot of input from affected parties. After much discussion and debate, the Food Safety Modernization Act passed in 2011, with multi-year implementation plan starting with education.

One of the key differences put into place by the law is that food safety is no longer a reactive process of addressing outbreaks when they occur—the idea behind much of the direction in the law is to prevent as many outbreaks as possible from happening in the first place, and then responding quickly and efficiently when they do. This concept builds off Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) plans that were implemented in juice, fish, and milk industries in earlier decades. Changing the focus to prevention means fundamental changes in how those who process food for human consumption must do business. The law also significantly increases the FDA’s authority to monitor food that comes into the U.S. from other countries.

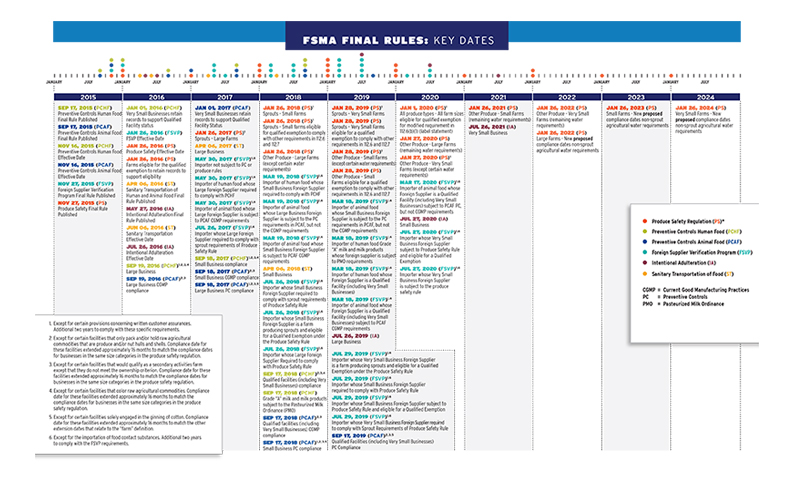

Passing legislation is one step, and the next is implementation. Implementing a law such as the Food Safety Act means that the regulatory agency (or agencies) involved develop agency rules, which have the force and effect of law—these are the federal regulations that govern food producers under FSMA.

A Short History of Food Safety Laws

The government agency spearheading compliance is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is the same body that was first tasked with food safety by Congress.

In 1906 the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed to regulate interstate commerce of food and drugs, and the oversight provisions in that law led to the eventual formation of the FDA. Prior to the passage of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) in 1938, there was little regulation that governed the safety of foods, medicines, and cosmetics.

In 1937 a pharmaceutical company developed a sulfanilamide medication—a form of an antibiotic—that contained a poisonous solvent called diethylene glycol.

It seems hard to believe now, but at the time the level of toxicity was not widely known or understood—and it was added to a medication that was ingested. More than 100 people died after taking the medication, and public outcry led Congress to pass the FFDCA, which among other things required products to be tested before they could be sold to the public.

Over the intervening years, additional laws have passed that were more limited in scope, such as the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act of 1966 and the Food Quality Protection Act in 1996. The Food Safety Act that was passed in 2011 is the most substantive overhaul since the 1938 law was passed.

What Are Some of the Key Provisions of the FSMA?

The three primary foundational rules that the Food Safety Act covers are the: Produce Safety Rule, the Preventative Controls Rule, and the Foreign Supplier Verifications Program rule. The Produce Safety Rule governs food and farming operations that grow, pack, or hold food, and the Preventative Controls Rule governs facilities that process food that is then distributed for human consumption. The Foreign Supplier Verifications Program rule governs those who import food into the U.S.

The scope of the Food Safety Act is considerable, and the FDA was granted considerable new authority under the law. As noted earlier, industry participation with risk assessment and prevention is a key goal.

The law requires mandatory preventative controls for food facilities, which include the need for written prevention (Risk Analysis and HACCP) plan that takes into account what hazards might be present that could compromise food safety.

It also requires a clear plan—in writing—as to what steps and controls must be in place in order to mitigate any hazards including validation of effectiveness, verification of on-going practices and a recall plan should these measures fail.

In addition to industry mandatory participation and prevention, other areas of broad authority for FDA are in inspection and compliance; response when problems are identified; regulating imports; and spearheading necessary partnerships with other agencies (international, state, and local) to ensure compliance.

Is Training Available to Assist with Food Safety Act Compliance?

The Food Safety Act was designed to improve the U.S. food safety system by emphasizing three core strategies: a focus on risk assessment and prevention, increased surveillance to detect problems early, and better response and recovery when problems do surface.

Because the scope of the law is enormous, touching on virtually every aspect of getting food from a farm to the table, training is available, important, and required. The FDA does not conduct trainings themselves, but instead partners with public-private groups and alliances that administer training of FSMA-compliant curricula. Trained Preventive Controls Qualified Individuals (PCQI) stationed in the plant and who are available for audits and inspections are integral to the success of the information transfer to the food production plants required to implement FSMA.

The established Alliances are where the majority of food producers will receive training. The Produce Safety Alliance (PSA) and the Food Safety Preventative Controls Alliance (FSPCA) are two well-established programs, each of which has a target audience. PSA offers a training course for growers that covers agricultural best practices and produce safety requirements and developing a farm food safety plan. FSPCA focuses on training for Preventative Controls rules compliance, which has two separate tracks, one designed for those who handle and produce animal food, and another for those who are involved in the production of food designated for human consumption.

Agencies focused on certain food manufacturers have a deep understanding of the microbial, chemical, and physical hazards challenging the industry and putting the food at risk. In partnership with suppliers, and food safety device manufacturers, like Charm Sciences, risk management strategies are developed, monitored, and maintained.

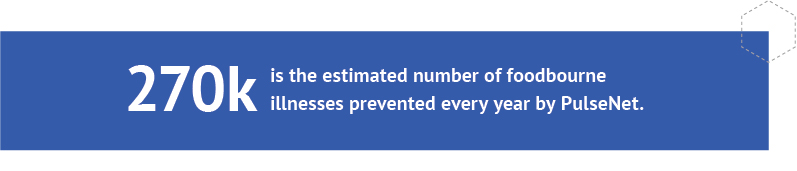

Additionally, other government organizations have started systems aimed at preventing outbreaks. Each year, around 1,500 clusters of diseases are discovered by state health agencies. The CDC also started the program PulseNet, a system that uses DNA fingerprinting of bacteria causing illness to detect outbreaks. Since starting in 1996, PulseNet has been able to prevent an estimated 270,000 illnesses.

Moving Forward

Although the Food Safety Act has been the law for a number of years, there are still parts of it that are yet to be fully implemented. There is a requirement that rules enacted be based on data and science—and sometimes that can make developing a rule tough. One of the most significant components of the law that remains on hold is the development of standards for testing agricultural water.

When government agencies propose rules, they are posted for public feedback, and the feedback the proposed agricultural water testing rule received was that the testing criteria were too complex and difficult to implement—so FDA has issued an extension for compliance and is revising the rule.

Consumers want food they can trust, whether it’s for their table or for their pets. While a prevention mindset and mandatory recalls when there is a problem are good steps, much of the reputational burden will fall on the industry. The fewer recall headlines there are, the more the public’s trust will build.

Producers can take the important steps of making certain they are compliant, receive the necessary training, and develop sound plans for monitoring and remediation.

Keeping Your Products Safe

The Food Safety Act’s focus on microbial and chemical hazard prevention is one that Charm knows a lot about—our food safety solutions are designed to meet a wide range of needs. Contact us today to learn more about how our sanitation monitoring, microbial detection, and chemical prevention solutions can help you meet the requirements of the FSMA.

About Charm Sciences

Established in 1978 in Greater Boston, Charm Sciences helps protect consumers, manufacturers, and global brands from a variety of issues through the development of food safety, water quality, and environmental diagnostics tests and equipment. Selling directly and through its network of distributors, Charm’s products serve the dairy, feed and grain, food and beverage, water, healthcare, environmental, and industrial markets in more than 100 countries around the globe. https://www.charm.com